Effective Charts Never Overwhelm An Audience

how do I get to know my audience when working remotely?

Through virtual and in-person workshops around the globe, we have taught tens of thousands of people how to communicate effectively with data. This series captures some of the noteworthy questions we hear during those sessions—and our answers.

One of your lessons that I really appreciate is the importance of understanding our target audience, and thinking critically about the context of every communication we deliver. My company has just adopted a permanent work-from-home policy, and I'm wondering: how do we get to know our internal audience—management, peers on other teams, and so on—when everyone is working from home?

This question came from an attendee of our most recent public workshop. Her company is among the growing number of organizations adopting a permanent work-from-home policy, citing increased productivity, reduced facilities expense, and improved employee morale. While she was on board with the change, she also wondered if this lack of in-person interaction might become a challenge, when it came to building a true understanding of her audience's needs and motivations.

Prior to joining the (distributed) team at SWD, I worked from home as a sales performance manager at Bank of America Merchant Services for five years. From personal experience, I can say confidently that this challenge isn't as daunting as one might think.

Here are the three ways I've had the most success getting to know an audience that isn't physically co-located with you. In this case, I'm defining "audience" as the primary person you are communicating data to in an organizational setting:

1. If you're a level or two removed from them, get to know their direct reports (or peers if an individual contributor).

Aside from strengthening your connections within the organization, getting to know new people closer to your intended audience gives you a way to find out helpful information, like what level of detail they like to see, what motivating factors they may have, and more. It also provides you with an advocate on their team. You can accomplish this by seeking out common ground—shared projects, mutual connections (LinkedIn helps with this!), or similar interests. Including these areas of common interest in your introductory emails, or in subsequent conversations, can be a simple but effective way to break the ice and establish rapport with your remote colleagues.

2. Find ways to be included in meetings with them. Shared experiences create bonds, even when those experiences might be a bit mundane.

Even if you aren't presenting, your presence in the meeting signals an interest in the topic area, and your name and face become more familiar to your audiences. Additionally, being an active listener during the meeting means you'll gain insight into their thought processes and pick up helpful context that will make your communications more impactful when you do share data with them. Virtual meetings are often easier to join than in-person meetings, so use this to your advantage!

3. Don't be shy—ask for feedback!

Whenever the opportunity presents itself, ask your audience directly for their reaction to, and assessment of, your deliverables. Stress to them your reason for asking: to ensure that future communications are more valuable to your audience. Finally, of course, you'll need to make sure you then execute on that feedback in future communications.

While it might seem like a tall order to get to know someone when you're not co-located, it can be done if you're willing to put yourself in situations where your audience is more visible to you. Creating those opportunities virtually requires you to be more direct about what you want in terms of access, information and feedback.

Are there other ways that I haven't listed here? Leave a comment with your thoughts!

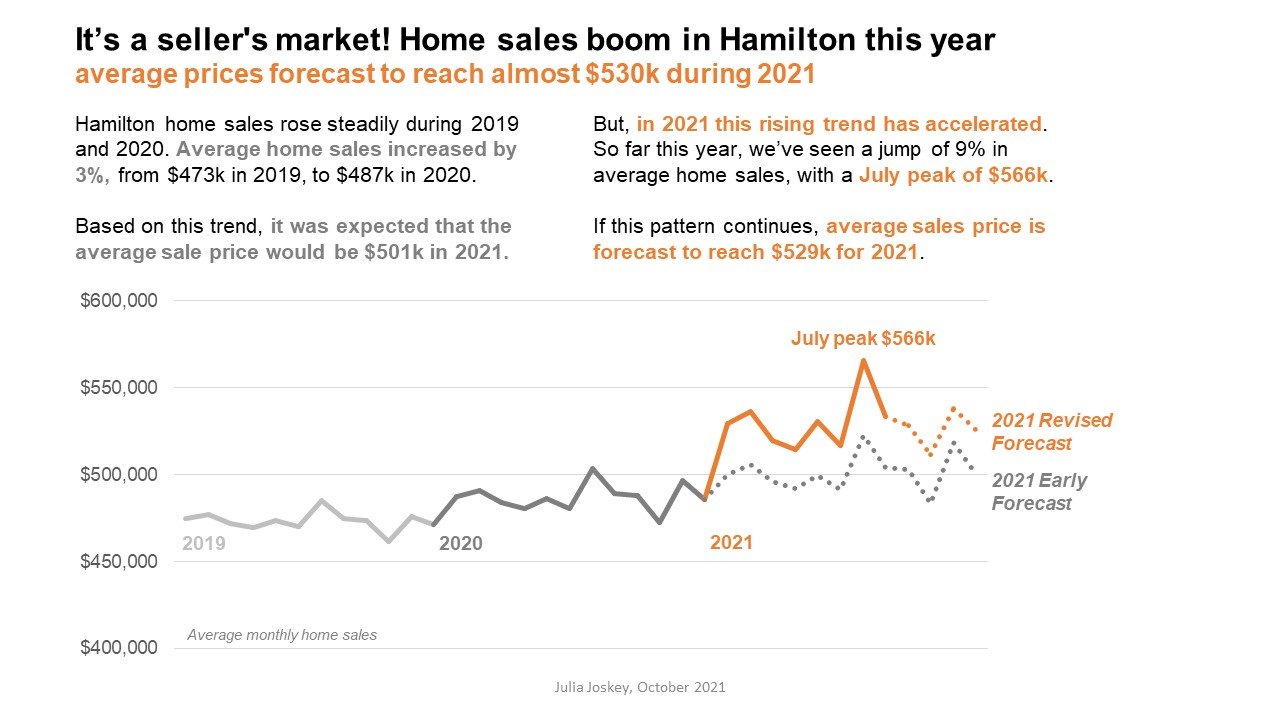

hamilton homes makeover

Combine home sales data with the opportunity to improve an underwhelming graph, and what do you get? You get 57 entries into this month's #SWDChallenge. Starting from a seemingly simple line graph (shown below), we asked our community to try their hand at strengthening the message and the call to action implied by three years of housing market data in Hamilton County.

We created and discussed one possible re-imagining of this graph ourselves, which we broadcast live (and a recording of which is available on our YouTube channel). But as we always say: when it comes to communicating with data, there is never any single "right" solution. People can find any number of paths to a clear, effective, persuasive, and memorable visual. Moreover, "success" in communication will always depend on your audience, your goals, your insights, and your expectations.

Let's explore some of the approaches folks took this month; and as we do so, consider how you might apply similar techniques to the communications you build in different situations.

1. Apply the power pairing of color and words to make the message stand out.

Austin applied color and words to make his key message stand out.

You can spend a long time learning and practicing all of the elements of the full storytelling with data process for communicating effectively—reading our books, taking our workshops, honing your skills in our community, and so on—but the quickest way to effect a significant improvement in how your visual creations are received is to use the power pairing of color and words intentionally and specifically.

In this challenge, a number of our participants kept the same basic chart type as the original example: a line graph. However, as Austin did in the example above, they applied color and words to their maximum effect:

-

COLOR Rather than using color for decoration or to distinguish between categories of data, many of our contributors' makeovers used color sparingly. They also limited their palette to one or two key hues, to signal what's important. When it comes to focusing attention, color is one of the strongest tools we have at our disposal—when paired with meaningful words, it can make the overall message of our visuals unmistakable.

-

WORDS Was there a key takeaway from this communication? Then write it big and bold at the top of the visualization. Were there key data points worth calling out? Then annotate those points with words, as close to the actual points as possible. A picture might tell 1,000 words, but your graph will always need a few dozen ACTUAL words so that your audience knows exactly what they're meant to learn, and act on, after seeing your communication.

2. Acknowledge uncertainty, and communicate it clearly.

Julia communicated the uncertainty of her forecasts by showing them as dotted lines.

A prior #SWDChallenge was dedicated to the theme of visualizing uncertainty, and many participants this month found an opportunity—or a responsibility—to apply these principles to the provided example.

Given that the current year's data was incomplete, some folks took on the task of projecting future home values (even through the following year, in some cases), but ensuring that those projections were visually distinct from historical data. Many used shaded regions and dotted lines (as Julia did in the example above) to show ranges of possible outcomes, and also used text to explain the rationale behind those projections.

3. Center the audience, and consider the problems that this data can help them solve.

Josephine considered the graph from an audience's perspective, and re-created it to focus on answering questions that home buyers and sellers would want to be able to answer.

Rather than approaching this makeover from the position of, "What do I want to say about this data," some participants (like Josephine) put themselves in the shoes of a consumer of this data, and so built their re-visualized work around answering the question, "What question could this data answer for a seller or a buyer?"

The challenge prompted participants simply to critique the original visual and make changes to strengthen the final product. Many of our contributors intuitively or intentionally decided to consider the audience's needs, and just that simple step itself can make any visualization better, because it provides a better and more meaningful framework for all of our subsequent design decisions.

4. Try something new.

Jill created several visually distinct versions of this graph, ranging from simple charts to this visual metaphor of a key.

In the spirit of experimentation, we did see a few people modify the original chart type, and some people discard it entirely! From smoothing the curves at each data point, to adding a second bar graph, to building a full dashboard, to adding Nigel Holmes-esque style mashups of line charts and keys (cleverly done by Jill), we saw evidence of the thoughtfulness and creativity our community brings to every challenge we issue.

We host these challenges for many reasons, and among those are to give everyone who works with data, or with visualization, a chance to play, to try new things, to explore, and to learn from one another, in a supportive and low-stakes environment. Without experimentation and practice, without new ideas and a diversity of approaches, we risk becoming stagnant in our work and uninspired in our tasks. Kudos to everyone who took a left turn on the way to their final creation this month.

Thanks to everyone who shared their work. We encourage you to check out all the submissions in the community. If you haven't yet participated in a challenge, maybe it's time to bite the bullet (graph) and show us the perfect use case for this specialized bar chart in the November 2021 challenge.

how do I graph three or more dimensions?

Through virtual and in-person workshops around the globe, we have taught tens of thousands of people how to communicate effectively with data. This series captures some of the noteworthy questions we hear during those sessions—and our answers.

When we have three or more dimensions to show, how do you recommend we do it? I worry that my audience might not be able to make sense of it all.

This is a great question. As analysts we are often asked to consider multiple dimensions at once, and investigate complex relationships among these variables. In doing so, we may use visual analyses to explore and find patterns and outliers. The graph types we use to do this tend to be complicated and less intuitive than a simple bar chart or line chart. They might make sense to a trained observer, but to an unfamiliar audience, they're at best confusing and at worst impenetrable.

Rather than use exploratory visuals to communicate multidimensional findings, try using one of these options, listed in increasing order of preference.

1. Bubble chart

A bulked-up version of a scatter plot, bubble charts are probably most strongly associated with the late Hans Rosling, who used them to great effect in videos for the BBC and for TED talks. Bubble charts place data points on an X and a Y axis, and then add additional characteristics (like color, size, marker type, and possibly motion) to encode even more dimensions.

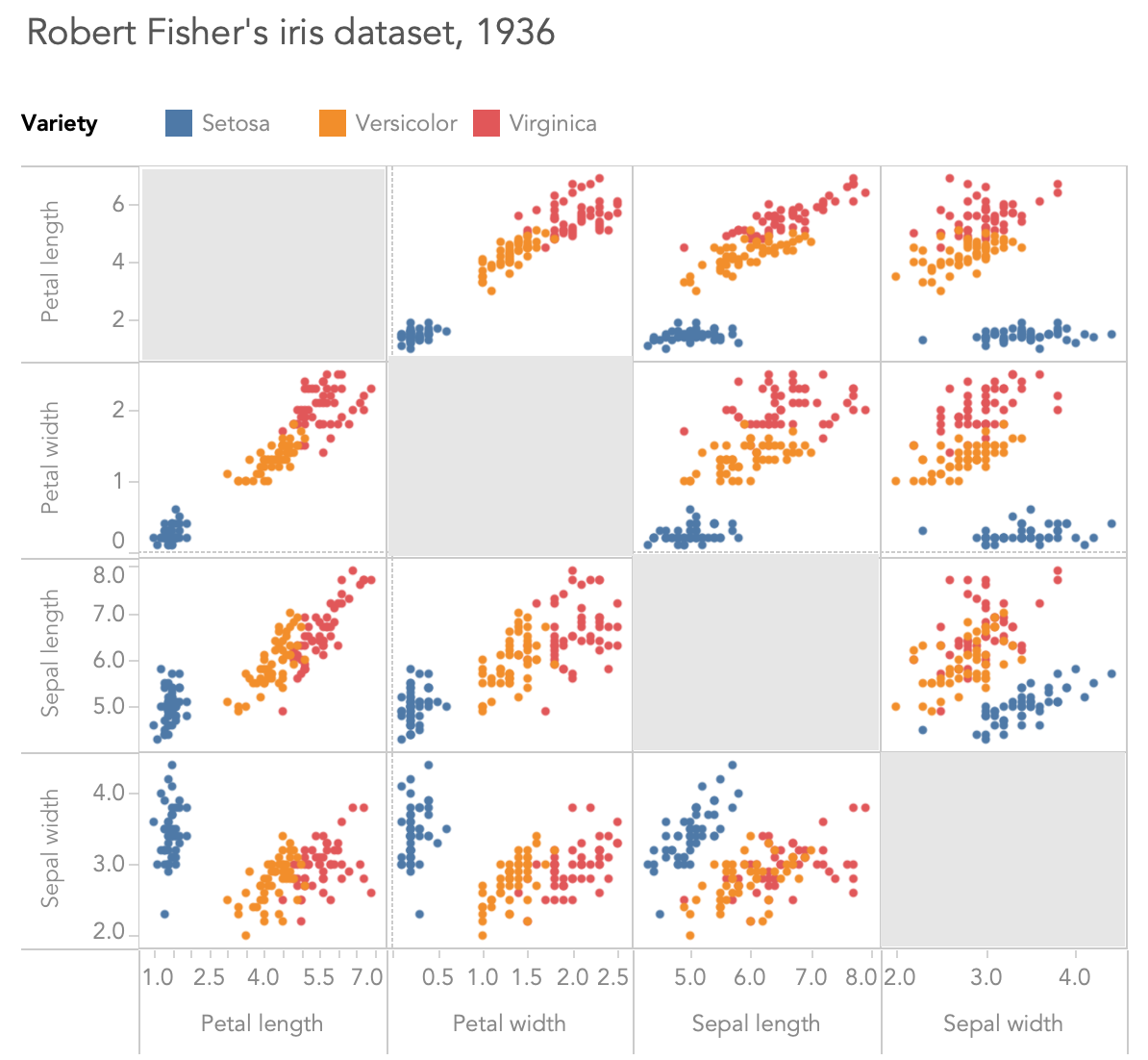

Here is an example bubble graph, using a famous dataset about petal and sepal dimensions of three different varieties of irises (created in 1936 by Robert Fisher).

The complexity of bubble charts introduces a hurdle that your audience has to clear. These graphs ask a reader to keep track of a large number of variables for each data point at the same time. In this particular example, a point's position in space relates to an iris's petal length and width, the color is the sepal width, marker size is the sepal length, and symbol type is the variety of iris.

For a reader unfamiliar with this data, it is hard work to draw any insights out of this graph. By presenting so many dimensions at once, you run the risk that your audience may opt out of doing this work and move onto something else.

2. Small multiples

Also called panel charts or trellis charts, small multiple charts can be used to break down multivariate datasets and show pairwise comparisons across any two dimensions.

Here's that same iris dataset as a small multiple:

In this view, each iris variety is a different color. We can compare any of our four measurements on the vertical axis with any other measurement on the horizontal axis.

A small multiple chart still requires some close reading to find the insights, but we can see a bit more information than we could in the bubble chart. For instance, we can see that Virginicas usually have longer and wider petals than Versicolors, while there is more of an overlap in those varieties' sepal lengths and widths.

3. Animating and/or using multiple graphs

Ideally, when we are ready to present multidimensional data to an audience, there will be some specific takeaways to highlight. Rather than present the exploratory graphs we used to find those insights, we can choose simpler graphs that make those findings unmistakable.

By choosing simpler graphs and revealing them one by one, or by building a single complicated graph piece by piece while you narrate each new element, you can take your audience on a journey of understanding.

A sophisticated investigation with a complicated outcome is much more likely to be understood and well-received by an audience if they can take it in gradually, via simpler visualizations, rather than if we ask them to try to grasp the entire multidimensional analysis all at once.

How do you visualize multidimensional data? Let us know in the comments below.

#SWDchallenge: build a bullet graph

In the spirit of drawing inspiration from questions asked at workshops, I'll pose one I recently received to you as this month's challenge: when might you use a bullet graph?

A bullet graph is a variation of a bar chart, typically consisting of a primary bar (often thinner and in the forefront) layered on top of another bar or stack of bars to show progress against a target or series of thresholds.

Not everyone is familiar with this chart type—it is not a standard option in most graphing tools—so in my response, I drew a generic one like you see above. I described the bullet graph as a replacement for the speedometer-like gauges that were popular in early dashboards, but are notoriously difficult to read. Most commonly associated with author Stephen Few, bullet graphs leverage our familiarity with bar graphs to deliver a lot of information in a compact space.

While my answer centered on general applications, for this challenge we'd like to know specifically when you would use one—show us a great use case for the bullet chart.

The challenge

Find some data of interest that will lend itself well and build a bullet graph. If you need help getting started, check out this list of publicly available data sources. You're also welcome to use a real work example if you can anonymize appropriately.

Share your creation in the SWD community by November 30th at 5PM ET. If there is any specific feedback or input that you would find helpful, include that detail in your commentary. Take some time also to browse others' submissions, too, and share your input via comments and datapoints over the course of the month.

Related resources

Here are a few related resources. If you are aware of other good ones, please share in your submission commentary.

-

SWD guest post by Bill Dean: the bullet graph (includes Excel step-by-step)

-

How to Make Bullet Graphs in Tableau by Ryan Sleeper

-

Jon Schwabish's One Chart At A Time: Gauge and Bullet Charts with Youyou Zhou

-

Bullet Graph Design Specification by Stephen Few

-

Bullet Graphs for Not-to-Exceed Targets by Stephen Few

We're looking forward to bountiful bullet graphs this month!

how do I know when I'm done revising my visual?

Through virtual and in-person workshops around the globe, we have taught tens of thousands of people how to communicate effectively with data. This series captures some of the noteworthy questions we hear during those sessions—and our answers.

I know it's important to iterate and get feedback when I'm creating a graph or building a slide. But with so many ways to modify the design—changing the chart type, adjusting the font style, using different colors, experimenting with alignment, and so on—I sometimes get caught in an endless cycle of iterating and refining. How do you know when you're done?

This question resonates with me personally, as I feel like nothing is ever really done—it's always just the "most recent iteration." If I revisit a graph I designed a year ago, I guarantee I'll make some tweaks. At some point, though, I have to stop, because my changes don't have much of an impact. Hence the saying, "Done is better than perfect!"

Here are three signs to help you (and me!) determine when your current version can be the final one.

1. You're out of time.

The range of possible formatting changes may seem infinite, but the time we have to make these changes isn't. Use time constraints, whether external or self-imposed, to your advantage.

If you have only a few minutes to optimize a graph or slide, don't spend time thinking about every potential revision to implement. Instead, focus on the quick changes that will have the biggest impact. Often, this means simple changes like modifying the use of color, adding annotations, or adjusting a slide title.

Time constraints can seem like a limiting factor, but it can also be freeing if you are someone who gets caught in an endless pursuit of the "perfect" visual.

2. You've received positive feedback.

I strongly recommend incorporating feedback into your creative process and throughout all stages of a project—the earlier, the better. It's often through those informal feedback sessions that you'll get insight into whether your approach is sufficient. If someone else understands the primary purpose of your communication, then you can probably stop there. Feel free to keep iterating, but know that you can also move on, confident that further revisions probably aren't critical.

There's always a balance between being effective and being a perfectionist, so talking it over with someone else will help you determine the right balance for your scenario.

3. The situation is low-stakes.

In addition to the above stopping indicators, I also recommend taking a step back and reflecting on the stakes of your work. Are you going to be communicating with an important audience member? Will there be high visibility? If so, then it's reasonable to want your final product to be pixel-perfect in every dimension. Not every data communication will call for such a high level of polish. Routine, ad hoc, or low-stakes slides and graphs don't warrant nearly as many iterations.

Think critically about how likely it is that the formats and changes you want to make will actually matter—or even be noticeable—to your audience. If you realize that it will make more of a difference to you than to them, it's probably time to move on to the next task.

I've shared some of my thoughts here, but I'm curious: how do YOU know when you're done with a visual? Share in the comments below!

how education looks

Last month, we invited you to envision education by sourcing some compelling data related to schools, academia, or learning and producing a visual that makes the "so what?" clear. Thirty community members accepted the challenge. Other than the theme of "education," we intentionally provided very few constraints for creators this month, so we were curious to see what specific ideas and approaches people chose to pursue.

Some topics were popular in multiple senses of the word—they came up in several submissions, and received positive feedback from the community. These included back-to-school shopping (Jacob's record-setting spending in 2021 and Ashley's parents vs teens fashion inspiration), COVID-19's impact on educational outcomes (Robyn's Australian lockdown length, Tran's delivery of remote learning, Jill's mental health in educators, and Kevin's impact on college enrollment), and demographic disparities (Nicole's mental health link, Lucia's university graduation rates, Zoe's lessening education gap, and Yuki's representation in STEM).

Creators of this month's submissions demonstrated many aspects of effective data storytelling, including clever choices of visualization types, sparing and focused uses of color, and the smart application of words to frame the communication. Let's take a look at a few of the submissions that exemplified each aspect.

Visual choice

An effective visual will represent the data in a way that can easily enable readers to experience an "a-ha!" moment of understanding. Jennifer paired simple text with a bar chart to display how much American teachers spend out-of-pocket on classroom supplies.

Words

Words bring your data to life—they're the best way to tell your audience what you want them to understand, and are vitally important if our data stories are going to be at their most effective. Lee's We're failing to value our teachers submission made good use of annotations to provide supporting context. Monica paired a strong takeaway title with a striking choice of color (red) to highlight that across the board, African-Americans without a college degree have more economic insecurity concerns than those with a degree.

These examples are just a sampling of the visuals we received this month—big thanks to everyone who shared their work. We encourage you to check out all the submissions in the community. If you haven't yet participated in a challenge, the time is now to flex your makeover muscles and show us how you'd improve this underwhelming graph in the October 2021 challenge.

Did you miss it? Watch the replay from our recent YouTube livestream where the entire storytelling with data team was together illustrating how to transform underwhelming graphs into compelling data stories. Subscribe to our YouTube channel to never miss out on practical tips and tricks that you can incorporate into your role.

Effective Charts Never Overwhelm An Audience

Source: https://www.storytellingwithdata.com/blog

Posted by: jonessuas1985.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Effective Charts Never Overwhelm An Audience"

Post a Comment